Crash of PSA Flight 182

Article by David Johnson

The mid-air collision of a small private plane and a Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) jetliner in the skies above North Park September morning in 1978 shattered San Diego like no single incident has before or since. Wars, terrorist attacks and political assassinations have had a far greater impact on the country as a whole, but this was a decidedly San Diego calamity that is seared into the collective memory of all above a certain age who lived here in those days.

The accident was a stark reminder that, while we have one of the great scenic airports in the world, that beauty comes with a risk. Planes landing from the east, as virtually all planes do, pass within a few dozen yards of buildings and busy streets before touching down at Lindbergh Field. The accident was a grim reminder that at this location there is no room for error. In the aftermath of the crash, whether you lived somewhere along the flight path of arriving or departing jets or were a passenger on a plane yourself, you began to view the experience through a different lens. And if you were a reporter or first responder working the crash site that day, you were scarred by grisly images you would take with you to your grave.

Beyond the fact that the jet blasted into a North Park neighborhood like a bomb, this tragedy involved a San Diego based company and many of its employees lived among us as neighbors. PSA enjoyed an excellent reputation, being known for good service and friendly staff.

The company motto was “Catch Our Smile,” and its planes had smiles painted on their noses. Fares were cheap, passengers received complimentary drinks and snacks from cheerful and fashionably attired flight attendants, your bags rode free, you had decent legroom and if your seatmate was packing on some extra pounds it was not also your problem.

PSA began operations in May of 1949, flying a single leased thirty-one passenger DC-3 on a once per week route from San Diego to Hollywood/Burbank and then on to Oakland. A fare from San Diego to Burbank cost $5.65 and the leg from Burbank to Oakland ran another $9.95. PSA soon added a second DC-3, and for the year flew 15,011 passengers a total of 321,112 air miles.

By 1978 the airline was flying thirty-nine planes carrying 7.8 million passengers more than three billion miles on a number of routes, including several to adjacent states. In the fleet were thirty-one Boeing 727s, including the one designated on September 25, 1978, as PSA Flight 182. The aircraft had been placed in service by PSA in 1968, and had flown 24,000 flight hours in the decade since.

Flight 182 originated in Sacramento on the morning of September 25, 1978. It had an uneventful flight to Los Angeles where it offloaded some passengers and loaded on others. In the cockpit was a highly experienced crew consisting of seventeen-year PSA pilot James McFerron, First Officer Robert Fox (himself a nine-year pilot with thousands of flight hours) and Flight Engineer Martin Wahne who had logged nearly 7,000 flight hours in 727s.

The plane carried four flight attendants, all in their twenties, and 128 passengers including 30 PSA employees heading to or from work. In the cockpit jump seat was deadheading PSA Captain Spencer Nelson, one of PSA’s most senior pilots with 26-years of service with the company.

At 8:34 on an already warm Monday morning, the PSA jet departed from LAX for the thirty-minute flight to Lindberg Field in San Diego with First Officer Fox at the controls. One minute later a yellow Cessna 172 lifted off from Montgomery Field in Kearney Mesa. Piloting the small plane was student pilot David Boswell, and in the co-pilot’s seat was instructor Martin Kazy. The morning’s lesson was instrument landings which enable a pilot to land a plane when visibility is diminished. As they were operating under visual flight rules, no flight plan was required. In accordance with instrument training protocol, Boswell was wearing a hood that obscured everything but the Cessna instrument panel from his view. Kazy, however, had a full field of vision from his position in the cockpit.

Flights that passed through the skies over the San Diego metro area and terminated at Lindbergh Field interacted with two air traffic control entities. The Approach Control Facility on the Miramar Naval Air Base, which is eight air miles from Lindbergh Field, managed traffic over the general metropolitan area. The Lindbergh Field tower managed landings and takeoffs into and out of the airport. Depending on their positions in the sky that morning, air traffic controllers from one or both were monitoring the two flights and giving them instructions.

At 8:53 flight 182 reported to Approach Control from a position north of San Diego at an altitude of 11,000 feet and was cleared to descend to 7,000 feet. Four minutes later the jet informed Approach Control that the airport was in sight, and the controller cleared them for a visual approach to Lindbergh runway 27.

After completing the second of two practice landings at Lindbergh Field the Cessna was climbing at 1,400 feet on an eastward course over downtown San Diego before beginning a bank to the north. At 9:00 Approach Control directed them to maintain visual flight rules at or under 3,500 feet elevation and take a 70 degree course northeast back to Montgomery Field. Student pilot Boswell acknowledged both the course heading and altitude restriction.

At the same time flight 182 was descending from the northeast at an elevation of 3,200 feet in advance of executing a right turn that would align it with the approach to Lindbergh Field. It had been flying at a 90-degree heading since crossing into the Lindbergh Field traffic area over Mission Bay. Approach Control advised the jet, “Additional traffic’s twelve o’clock, three miles, just north of the field, northeast bound, a Cessna 172 climbing VFR out of 1,400 (feet elevation).” First Officer Fox responded, “Okay, we’ve got that other twelve.” Approach Control then instructed PSA 182 to maintain visual separation and contact the Lindbergh tower for landing instructions.

Meanwhile on the ground, Hans Wendt was less than a minute away from taking two of the most iconic photographs in San Diego history. The fact that Wendt was in North Park at all on the morning of September 25, 1978 was something of a fluke. Wendt was midway through a sixteen-year career with the County of San Diego’s Public Information Office, serving as the organization’s official photographer. Much of his routine work was done indoors, and he only happened to be outside and in proximity to the Lindbergh Field approach because of the County’s groundbreaking work combatting air pollution.

In 1972 the Board of Supervisors had become the first governmental body in the nation to adopt highly contested rules requiring that gas stations install equipment to prevent the escape of gasoline vapors during fueling. As no such system was yet widely available, the County’s Air Pollution Control District worked with private industry in developing the vapor recovery systems that are now standard on most gasoline pumps. Politically it was a big deal locally.

On that morning Wendt accompanied Board of Supervisors Chairwoman Lucille Moore to the unveiling of a new vapor recovery system at a service station at the intersection of University Avenue and Boundary Street in North Park. Among other press covering the event was a Channel 39 news team consisting of reporter John Britton and cameraman Steve Howell. As the event was wrapping up, a catastrophe began unfolding in the air above them.

Apparently unnoticed by anyone on the Cessna or at Approach Control, the student pilot Boswell had drifted from his assigned heading by twenty degrees and was now at the same 90-degree course as the 727. At 9:01:07 the Lindberg tower now had flight control over PSA 182 and cleared the jet to land. The tower further advised them, “PSA 182, Lindbergh tower, traffic 12:00, one mile, a Cessna.” This caused confusion in the cockpit. McFerron asked the crew, “Is that the one we’re looking at?” Wahne answered him, “Yeah, but I don’t see him now.” Back in communication with the tower McFerron said, “Okay, we had it (the Cessna) there a minute ago.” The tower responded, one eighty-two, roger.” And in a statement that would be carefully parsed later, McFerron told the tower, “I think he’s passed off to our right.”

The jet had now lowered the landing gear into place, but the Cessna was still a concern to the crew. In the cockpit First Officer Fox asked, “Are we clear of that Cessna?” Wahne replied, “Supposed to be,” and McFerron added, “I guess.” From the jump seat Captain Nelson said to the sound of laughter, “I hope.” McFerron concluded, “Oh yeah, before we turned downwind I saw him at about one o’clock. Probably behind us now.”

At that moment the Cessna was flying northeast above the intersection of University Avenue and the 805 freeway. It was climbing in elevation, though still lower than the jet, and was slightly to the right of the 727 which was descending on a southeast line. At 9:01.28 as the two planes began to converge, a conflict alert warning went off in the Approach Control facility. Controllers there believed both planes were adhering to the visual sight order and that each was aware of the other’s position. Fatefully they gave no avoidance maneuver orders to either plane. Nineteen seconds later at 9:01.47 the 727 hit the Cessna from above at an elevation of 2,600 feet above the intersection of 38th Street and El Cajon Boulevard.

The right wing of the jet struck the top of the Cessna, destroying the smaller aircraft and sending the pieces plummeting to the ground at 32nd Street and Polk Avenue. Incredibly nobody on the ground there was killed. The impact with the Cessna also caused great damage to the wing of the 727, and pieces of the jet’s wing were found in the Cessna wreckage. Pieces of the Cessna propeller were likewise found in the wreckage of the 727. The effect of the damage rendered the jet uncontrollable. As it banked into a death spiral, the fuel tank in the wing ruptured and caught fire.

While it is virtually certain that neither of the Cessna pilots survived the collision in a condition to contemplate their fate, the same was not true of those in the 727. “Easy baby, easy baby,” cautioned McFerron two seconds after the collision. He then asked, “What have we got here?” “It’s bad,” replied Fox. “Huh?” said McFerron. “We’re hit, man, we are hit” replied Fox as he fought to control the plane. Eight seconds after the collision McFerron advised, “Tower, we’re going down. This is PSA.” At 9:02.07, seismographs at the Museum of Natural History in Balboa Park recorded impact with the ground.

The sound of the midair collision had shocked the media party on the ground beneath them into action. As County photographer Wendt raised his camera and snapped two still photos of the dying jet, Howell trained his video camera on the debris from the falling Cessna. Wendt later said he never saw the Cessna. His first photo shows the jet on fire and plunging earthward against the backdrop of a clear blue sky. The second captures it rolling toward its right side in a steeper dive just before it disappears behind a building. Today there would likely have been dozens of cell phones documenting the tragedy, but Wendt’s photos and Howell’s grainy video are the only visual documentation of the last moments of the two planes.

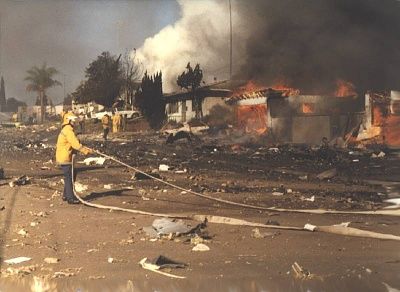

The 727 hit the ground about thirty feet north of the intersection of Dwight and Nile streets at a speed of 300 miles per hour. Because of its angle of impact, the fuselage of the jet landed in a twelve-foot by six-foot impact zone, and the resulting compression forces expelled mutilated people, luggage and cabin contents out its left side at a high rate of speed. Virtually everything on and in the plane was blown to pieces.

Collateral damage like house fires, downed power lines, pools of jet fuel and crowds of onlookers were expertly managed by police and fire crews. They deserve much of the credit for the fact that the crash’s aftermath was safely managed. Media crews were given full access to the scene and as a result the record of this crash is almost unprecedented for such a disaster. Not much about it is unknown.

In its thorough examination of the crash and its causes, the National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) later concluded the yellow Cessna might have been hard for the PSA cockpit team to see against a field of similarly colored roofs in the neighborhood beneath the jet. They also noted that the positioning of the pilots’ seats could have affected what they saw. But they found much blame to go around:

· The Approach Control staff had not advised PSA flight 182 to remain above 4,000 when passing over the Montgomery Field Control Area as protocol required. This alone would have prevented the accident.

· The Cessna did not maintain the course directed by flight controllers. Had it done so it would have passed about 1,000 feet under flight 182.

· The Cessna did not advise controllers of its course change. Had it done so, directions would have been provided to one or both planes to prevent a collision.

· The PSA crew did not advise the Lindbergh tower that they had lost sight of the Cessna. It was their responsibility to keep the smaller plane in sight or report the loss of visual contact, and they failed to do that.

· When one aircraft is overtaking another as was the case here, the overtaking plane has the responsibility to alter course. This rule required that flight 182 place itself at least half a mile clear of the Cessna, even though that would be close enough to set off a conflict alert warning at Approach Control.

· The Approach Control staff did not respond to the conflict alert warning it received nineteen seconds before the crash, more than enough time to order emergency evasive maneuvers from one or both planes.

In the end a single garbled word may have been at the root of the accident. The air traffic controller told NTSB investigators that McFerron had advised the tower that the Cessna was “passing” off to the right. In fact, McFerron had said the Cessna had “passed” off to his right, an indicator that he no longer had visual contact with the smaller plane. Had the tower heard this transmission correctly and understood its significance, protocol would have required them to direct the jet to a safe landing.

Today there are no visible signs of the disaster that occurred here. On the street where the jet crashed, there is a mixture of original and newer homes, and it is impossible to tell which are replacements of those destroyed and which are renovations or rebuilds that occurred in the normal course of events.

The intersection of Dwight and Nile which the jet obliterated in 1978 is shown below as it looks today, and the city has not chosen to note or commemorate the lives lost here in any way. The same is true of the intersection of Polk and 32nd street where the Cessna fell from the sky.

There is a memorial plaque in the Aerospace Museum in Balboa Park, and there is also a plaque near a tree at the North Park Library which honors those who lost their lives that day , but they are well removed from the crash sites.

In the wake of the crash the Federal Aviation Administration moved quickly to close safety gaps in the skies above San Diego. Within two months the FAA mandated radar control of all commercial planes in the vicinity of Lindbergh field. Elsewhere in the county where visual flight rules still apply at smaller airports, all planes must carry transponders that allow radar to track their movements. Landings are all steered into a corridor that extends well east of the airport where they pick up the airport’s Instrument Landing signal. And the collision alarm system not only warns both planes anytime a conflict over air space arises, pilots are given specific instructions to move them out of danger. All of these developments make “accidents” extremely unlikely, but deliberate or terrorist acts could be another thing.

It is hard to overstate the significance of the PSA crash to San Diego. At the time it was the worst air crash in American history in terms of lives lost, although the following May there was a greater loss of life in Chicago when a DC-10 crashed shortly after liftoff. Nearly forty years later the PSA crash is still one of the ten worst air disasters in North American history.

Dwayne Armstrong

If the Cessna would have not turn south and tried to clime over the PSA right wing because their is a void above the wing on a jet. This is why the Cessna doped on the wing and the front propeller hit the front edge if the wing and exploded. This cause the parts of the plane to go into the upper and right engine of the plan.

Thank You

Gael

How many of the same intersection picture do you need to show?